India Day 5 – Lost and Found

Day 5 – Lost and Found

During the night, when we are chugging downriver from Krishnanagar, there is torrential rain. Visibility at dawn is not much better. It’s what the Scots call dreich: thicker than mist, but not quite rain. In the wheelhouse, our pilot Nimai, is working hard to steer around the sandbanks, many of them invisible to ordinary mortals. But he sees them. Tiny variations in surface patterns and currents reveal their position. “You can never be sure,” he tells me, “New ones appear, those you knew disappear forever.”

Nimai was born on the river. Literally. On a ferry ghat. And then grew up messing about in boats. Just once he felt the urge to travel and went to Pune in Maharashtra to work in a factory. He didn’t last long. “I missed the river.” He laughs. “The river is my life.”

At Triveni we see the towers and spires of religious temples, and the Jamuna River joining, having journeyed all the way from the Himalayas independently of the Ganges. What we do not see is the Saraswati River. The mouth of that waterway was once here, but a change in river movement cut it off. Nimai confirms such things can happen. “One year I came downriver and the current had cut off a whole bend – twenty kilometres of river was missing. It was good for us, a quicker route, but the villages there had lost their river.”

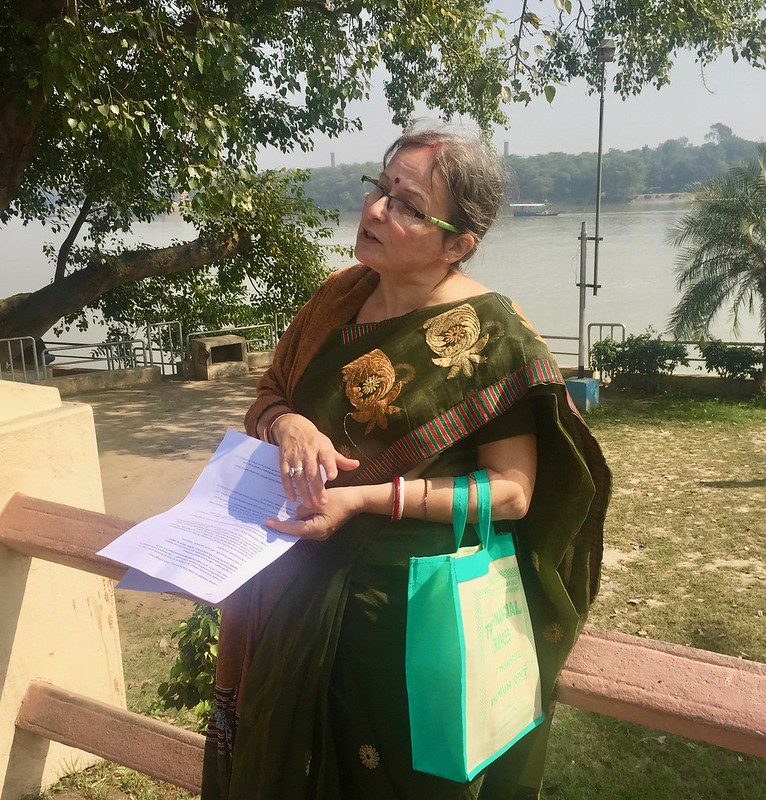

When we pull in, it is at a small ferry ghat at the end of Chandannagar where we are met by Neline Mondol who looks like a local, but is fact Belgian, having come here 27 years ago. She points out a derelict old colonial building. “That was the French passport office and I’ve managed to persuade the government not to knock it down.”

The French came in 1686 and stayed here continuously until 1952, except for a short period of British rule in the 18th century. We stroll along The Strand, a kilometre of broad stone pavement along the river lit by cast iron lamps that would not look out of place on a Parisian boulevard. A cow snoozes contentedly inside the memorial to Monsieur Roquitte, an Indian who Gallicised his name. I’d like to say that French influence is everywhere, but the truth is that only the older buildings reveal any influence. When the enclave became part of India, the new government closed down all French businesses. Just one French bakery remained to produce the essential baguettes and croissants, but they too finally succumbed three months ago.

Beside the church in the centre of town, there are speeches and a play. There are many references to Rabindranath Tagore. Apparently he often walked on stage here. During a lull in proceedings I sneak off to the chai stalls outside. They are busy with people eating chow mein, Bengal’s favourite snack food. There I find one of the Bengali members of our group, Korak. “Honestly,” he says, “Most Bengalis cannot go twenty minutes without mentioning Tagore. They find any excuse: ‘Oh look at this mosquito repellent: It was Tagore’s favourite brand’!”

We laugh and order chai in clay cups. “It’s like an obsession,” he continues, “And it means all the other great writers that we have never get a look in.”

So would it be better if Tagore was forgotten? Should he be lost, along with the baguettes and croissants?

“Actually, I like his poetry, but he’s not the beginning and end of Bengali literature, just like Satyajit Ray isn’t the only film maker.”

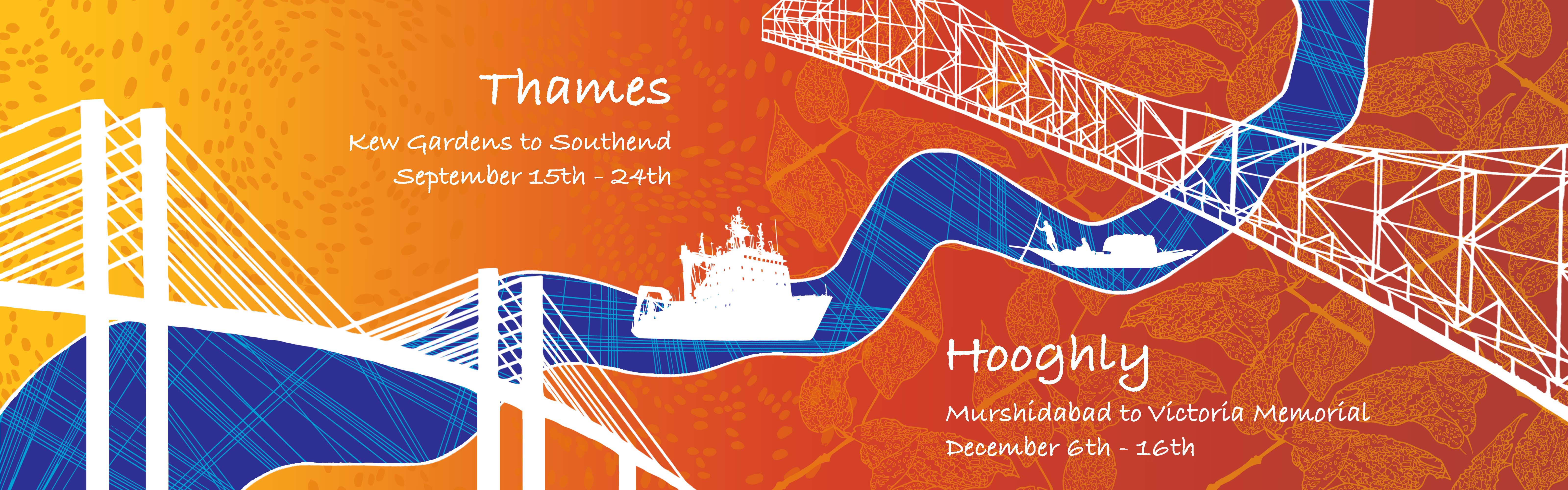

This journey keeps raising that question: how do you manage heritage and change. Are the two condemned to be at loggerheads? Perhaps an arts project like Silk River suggests a way out of the impasse by encouraging communities to be proud of their heritage while finding new pathways for creativity to flourish.

Back at the chai stall Korak is musing on the subject. “You know there is a snack food in Bengal – it’s not so popular now, but you can still get it. Kabiraji. You know where that Bengali word comes from? From the English word cabbage. It started out as a vegetable snack, but then we added chicken dipped in egg. Later we forgot about the cabbage. That’s kabiraji.”

Kevin Rushby

A selection of photos from today’s walk from Mike Johnston

Silk River App

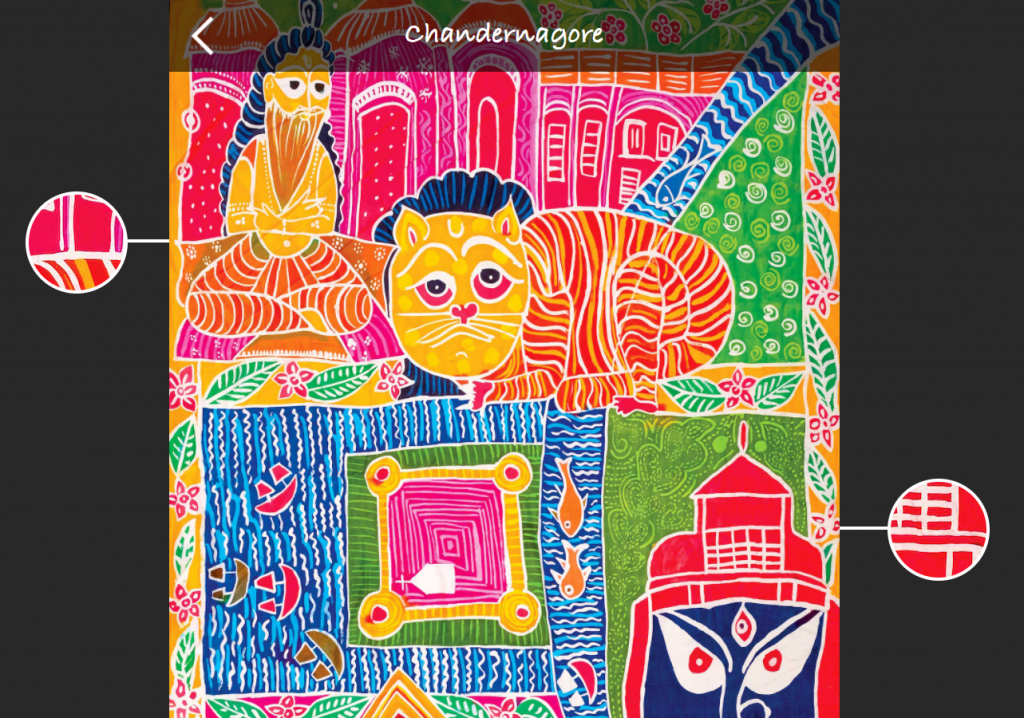

Explore the Chandernagore Scroll through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible

Photos below are from a research trip to the area by Mike Johnston.