India Day 4 – Specialities

Day 4 – Specialities

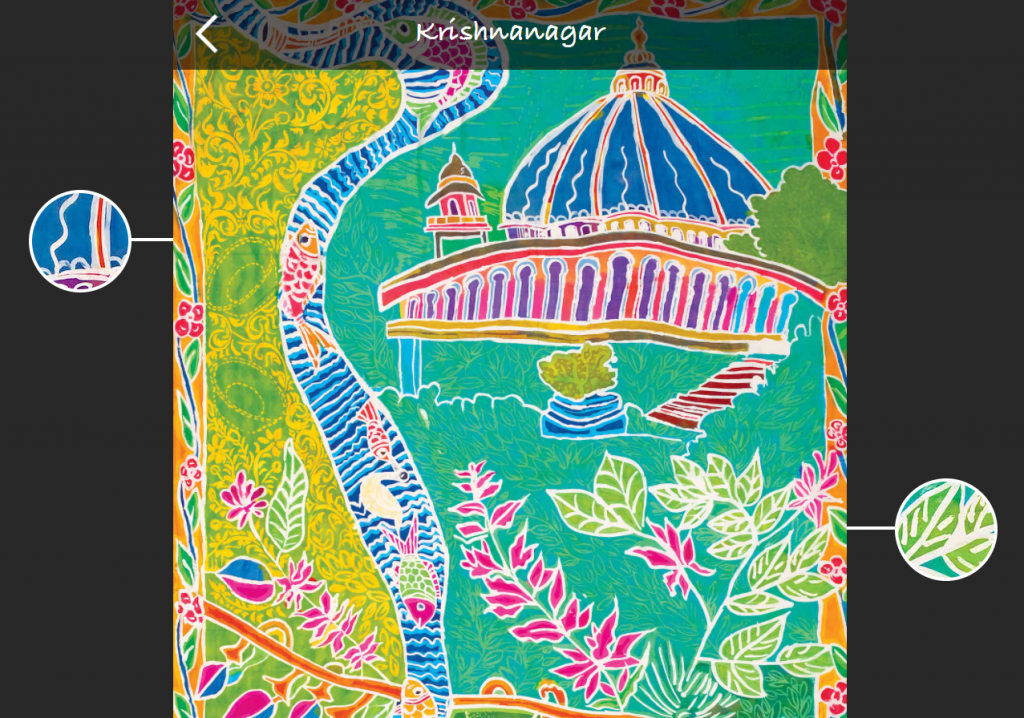

I like a town with a speciality. Nuremberg is wooden toys, York is chocolate, Buenas Aires is tango and London is second-rate politicians – no, hang on, every capital city seems to specialise in those. But Krishnanagar, a small city at the confluence of the Hooghly and Jalanghi rivers, produces Rabindranath Tagores, also Netajis, Vivekenandas and Gandhis. I don’t mean it turns out a useful supply in Bengali poets, military leaders, gurus and heroes although that would be handy, I mean it makes clay models of them. Back in the 18th century a deposit of clay was discovered in an ox-bow lake that was perfect for modelling. At that time the local ruler, Maharajah Krishnachandra Roy, was released by the Mughal emperor, Akbar, after an embarrassing charge of tax evasion (thus proving he was only human). It prompted him to have a dream about the goddess Durga and kick start a Hindu revival. Part of that revival was a demand for idols, and so the clay came into its own.

On a rainy morning we walk into the quarter of Krishnanagar where there is a thriving cottage industry in sculpting. At the studio of Subir Paul, an apprentice is applying the finishing touches to a five-foot tall figure of Manasa, the snake goddess, much beloved of farmers in South Bengal where venomous snakes are common. The workshop is a wonderful opportunity to assess the reputations of both worldly and heavenly figures, in this corner of Bengal at least. Churchill and Lenin are gathering dust on high shelf while Mother Teresa looks like she needs a hefty discount. Goddess Durga is doing fine, but rumours of a Donald Trump are unfounded – they don’t think there’s enough clay in the lake for that.

As I chat to Subir, a cart goes past bearing an image of black Kali en route to some puja. We are ready to form our own procession with a marching band of drummers who lead the Silk River flags through the town causing a lot of interest, some bemusement and a traffic jam. Walking along, I talk to Ruchira who runs Think Arts, an arts organisation in Calcutta. “I think we have a problem in India with our crafts,” she says. “They don’t move on. There’s no change or development.”

It’s a tricky question. The musicians we heard yesterday were adamant that they had to keep their stock of traditional river songs unaltered, but the trouble with that kind of classical purity can be that it results in stagnation and an irrevocable slide into obscurity and irrelevance. I think of those English folk artists who sing about wassailing when no one has the least idea what a good wassail looks like. Heritage can be an awful straitjacket.

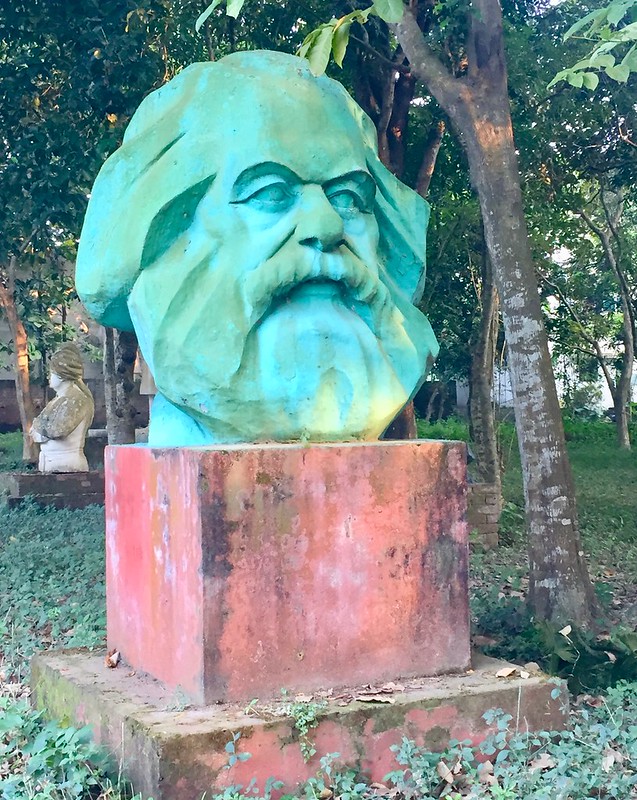

From the town centre we head out by bus to the palace built by the aforementioned Maharajah Krishnachandra Roy, one of the most popular tax evaders Bengal has ever seen. According to legend his loyal subjects clubbed together and raised the fine to release him. The palace is on the outskirts of town. We walk in past the hall where devotees still flock to the palace’s Jagatdhatri Durga puja every autumn. Outside the palace itself, the gardens are filled with cannons and cabbages, and not ornamental ones either, just big healthy Savoy vegetables – I mean the cabbages not the cannons.

Up the steps we walk past a life-size clay model of the Maharajah Krishnachandra Roy inside a glass case, then into a large reception hall filled with chairs of many styles and colours. There are many intriguing objects on display: several leopard skins, a revolver, a bowl of old bullets and some handsome hand-painted chairs. Then a dignified couple appear in a doorway and advance into the room smiling. They are Amrita and Saumish Chandra Roy, descendants of the Maharajah Krishnachandra. Some locals, not all, still refer to them as the Maharanee and Maharajah.

We sit and the couple explain a bit of family history. “It was the Mughal emperor who gave permission for turrets on the palace walls,” says Saumish. We crane our necks to admire his turrets, but I can’t see them. Later I’m allowed to sit on the throne that Emperor Jehangir presented to the Maharajah. “Now you are a king,” says Saumish. If only it were that easy, and I’m not sure I’d like the job of constantly explaining my family heritage. Mind you, I’d like to see my neighbours’ faces when I install a life-size image of my great grandad on the front step.

Leaving the palace we go to the workshop of Ashis Kumar Bagchi who makes headdresses for ceremonial occasions, particularly important pujas and weddings. Thirty-seven years ago Ashis had to drop his education and start making a living to support his family. As he had always enjoyed watching the headdress makers at work, he decided to try that trade. He soon proved adept, but it was when Ali Pretty (now Silk River director) came to visit in 2003 that his business really changed. Ali had seen the headdresses and was convinced that the carnivals of the Caribbean had been heavily influenced by Indian styles via the indentured labour of the 19th century. She ordered 250 items for the Notting Hill London carnival and Ashis was launched into an international career.

In the old days, he tells me, they were made from natural stuff like shola wood, glass and grass, but those old materials required greater skill and time. With that modernising change, the craft not only survived but thrived, sending items out to the huge Hindu festivals and all over the world. It’s proof that Ruchira is right: a little development can breathe fresh life into a tradition.

With darkness, and the rain, still falling, we head back to our boat which is anchored at the end of a dark lane beyond a vegetable market. I get distracted by a light coming from a shed where two men are sitting cross-legged beside a pile of carved wooden pegs. Intrigued, I go inside and discover that they are making handloom shuttles: polished wooden blocks of tamarind wood with sharp metal points on each end. The equipment is minimal. They use a big toe to hold the wood while working. They have been doing it for forty years and the last shuttle they made is precisely the same as the first. There has been no development and no change. And yet the shuttles are exquisitely beautiful, the strange grain of the tamarind making each a unique item. Change or immovability? I don’t know. Can we have both?

Kevin Rushby

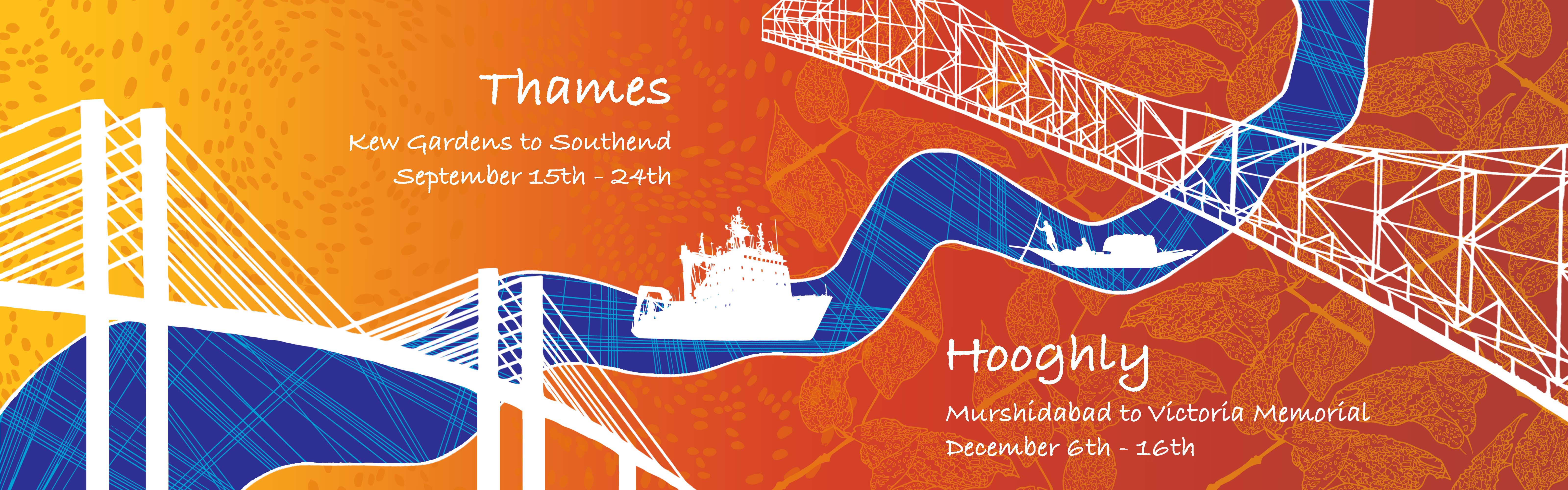

Silk River App

Explore the Krishnanagar Scroll through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible

Photos below are from a research trip to Krishnanagar by Mike Johnston.