India Day 1 – An Omen

India Day 1: An Omen

When I tell people in England that I’m going to India, they always seem to say something like: ‘You must love it.’ And after a pause: ‘When were you last there?’ Their implication, I reckon, is that India is changing fast and the India I knew may no longer be around. But the first morning after arrival I step out into Calcutta and know all is well. The man who sells cauliflowers and bananas is still there on the corner, the chai comes in terracotta cups and the hanging gardens, as I call them, the old buildings festooned by nature in a rich facade of aerial roots and foliage, remain. Calcutta may one day be thankful for its slower rate of development than other neighbouring cities.

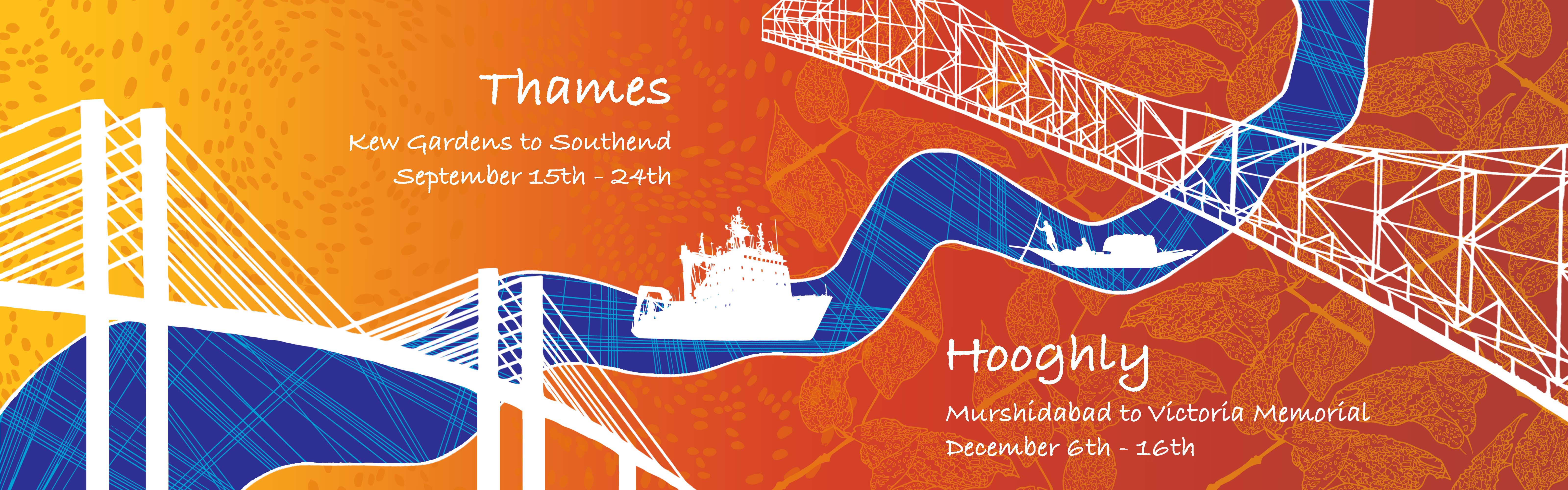

At St. John’s church in a lost corner of the graveyard I find the tombstone of William Hamilton who, it informs me, saved the King of Indostan from a malignant distemper. It takes one of my companions, Elizabeth from London, to notice something peculiar. Hamilton died on the 4th of December, 1717. It is 300 years ago precisely. I take it as an omen. Old Doc Hamilton did much to assist friendship between Britain and India, now here I am on the second leg of our Silk River walk, a project that aims to celebrate a relationship between the two historic rivers of Hooghly and Thames – and also stimulate a renewal through art.

We travel 200km upcountry by train. Our journey begins in Murshidabad, an area whose riches, particularly textiles and silk, started that relationship back in the days of Hamilton. We arrive at night in a rural area and find our hotel. Morning reveals a land after harvest: ox carts groaning under loads of rice stalks, fields picked clean by egrets and pied starlings, and – yes – roads choked with trucks, autorickshaws and buses. Some houses have cow dung cakes stuck to their walls, their roofs are curved, the bangla roof, from which English derived its word bungalow.

We walk, flags flying, into Azimganj, now a small and unimportant town on the river. Its streets are narrow and light on traffic. People stroll or cycle. The first thing that tells me this place may have something special is an old wall, its top a serpent’s back, its facade marked by the centuries. Then there are shuttered windows, columns, arches, crumbling balconies – Azimganj was once a major trading post. When William Hamilton was still alive and doctoring royalty, the Nawab of Bengal moved his capital here from Dhaka and the place flourished. Jain merchants came from Rajasthan and built beautiful mansions along the river, homes paid for with the profits from silk, among other things.

Pradip Chopra of the Murshidabad Historical Development Society gives us a tour. The Jains never kill a living creature, so silk presented a problem: the process normally kills the larvae. But they were an ingenious bunch and invented ‘non-violent’ silk. The larvae was allowed to emerge and fly, then the silk was spun from the empty cocoon.The fame of Murshidabad silk spread, the Jains flourished. Then came the Battle of Plassey, famine, rebellions, silting of the river and a move of the capital to Calcutta. By the 1970s when Naxalite Marxists began operating in the region, the Jains had all gone and their mansions were forlorn crumbling wrecks.

Almost two years later the house is reborn, its mosaic floors and pillars of Burmese teak polished and beautiful. Within a few months it will open as a hotel, part of an attempt to bring tourism to a forgotten but wonderful corner of India. Old crafts and skills have been revived. Silk River has played its part, ordering 300 yards of Murshidabad silk, the first such order in a generation. Old looms were dug from store cupboards, artists had to consult their grandparents for lost techniques, then learn some new ones too. A new sense of enthusiasm and energy has gripped the community. Other buildings are being restored; the magnificent terracotta temples nearby are being visited again. There’s a sense progress without loss of heritage and tradition.

But what about the white owl?

Darshan looks rueful. ‘I’m afraid he went away during the work.’

After dark I walk the streets looking for a place to write this story. I just need a table and chair and no distractions. I bump into Darshan’s sister, Lipika. Can she help? She ponders, glancing up at the back of Bari Kothi, the part still under restoration. “The roof is quiet and has a lovely view of the river.”

Up on their roof I settle down with a terracotta cup of saffron water and my keyboard. There is only one small distraction: a regular screech coming from the darkened courtyard behind. I sigh. India. Is there ever peace and quiet here? I stumble over the cement bags and rubble to the parapet and lean over. There, no further than a Silk River pole away, is the source of the noise. A white owl. I take a photograph. I like proof of my omens. His head swivels and his great eyes glare at me. Then he starts screeching again. He is not going anywhere.

Kevin Rushby

Photos of the Silk River Launch.

The Making of Murshidabad Silk

Various accounts of the history of silk in India claim that silk weaving in Bengal existed from ancient times.

Records show that the Silk Weavers of Murshidabad were operating in 18th century when Nawab Murshid Quli Khan shifted the capital of the Dewanee of Bengal from Dhaka, now in Bangladesh, to a new capital he built on the east bank of the River Bhagirathi and named Murshidabad.

Murshidabad is famous for its cowdial saris made of fine mulberry silk with flat, deep- red or maroon borders made with three shuttles.

Read more about Murshidabad silk on our website HERE.

Camera and production by Korak Ghosh, Joydeep Bhowmick and Mike Johnston.

Run time: 03:38

Silk River App

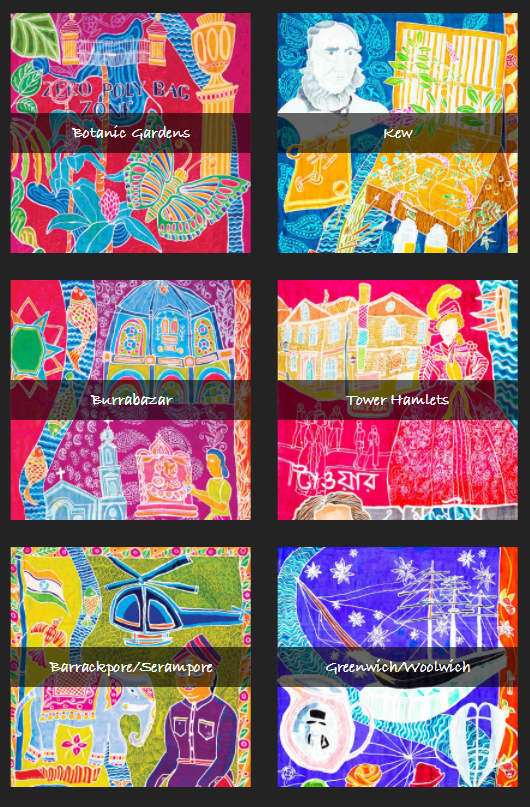

Explore the Silk River Scrolls through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible