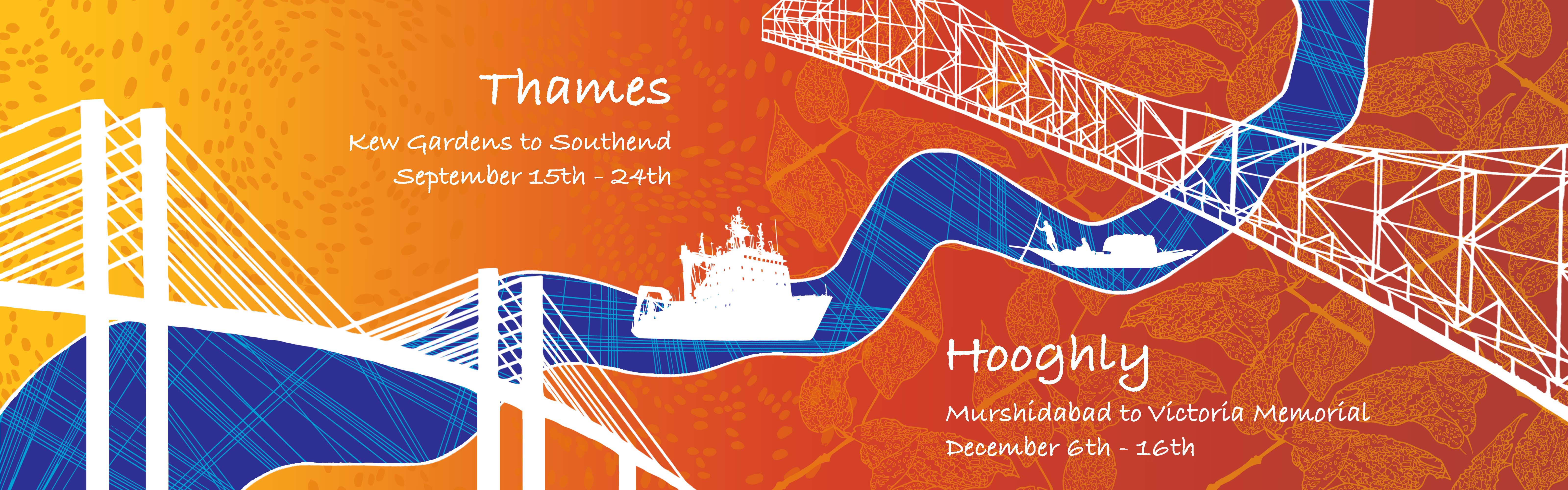

India Day 2 – Serendipity

Day 2 – Serendipity

One wonderful thing that happens when you travel through a landscape with something of a purpose is the chance encounters, the unexpected conversations that suddenly open up unseen worlds. Like with Darshan last night in Azimganj when he let slip about the elephant. We were standing on a balcony without a parapet. I was looking at the edge, wondering if anyone ever fell off into that courtyard below, but Darshan had something else in mind. “That’s where the elephant lived,” he says. “My great grandfather and the elephant were firm friends. Every morning they took breakfast together.”

“What did they eat?” I asked. In a Jain household I don’t suppose he got a full English, but how would a pachyderm tackle a puri?

“Kalojam,” he says. “A sweet. They’d eat together from a large bowl.”

He was a special creature, apparently, so clever that people thought he had a pearl hidden in his skull. When he eventually died – I don’t like to ask if it was from a dietary problem – he was given a full burial with a guard of a hundred men who stayed on for a year to prevent tomb raiders searching for the pearl. Conversations like that. Keep talking to people long enough and they happen.

Pallab Roy, grandson of the last Rajah, shows us around. The place is open daily to the public and there’s a small guesthouse on the side. There’s no pretensions here: even the Royal Bengal tiger dozing on the rug turns out to be a cuddly toy. Well, I think so. I don’t take the risk of poking him.

Pallab has done a lot to restore the house, but he’s taking the sleeping tiger approach to some things. The original wall paintings are not going to be touched in case they disintegrate. We stand by the family temple. There’s a kingfisher on the top of the dome watching us. “My grandfather had to find a way to make a living so he started a business selling confectionery and medicines.”

We talk about that for a while. And then he lets slip about the silk. The family sell silk. Where? There’s a shop. Where? Next door. We stroll up the street. “Just behind these houses,” he says, “There are ten ancient Shiva temples.”

I briefly entertain a fantasy of me forcing my way through undergrowth to uncover a fabulous ancient site. But that’s the other thing to mention about these conversations: there are possible corners that never get turned because something else happens.

In the shop I’m shown silk. “Where is it made?” I ask, expecting to be told China.

“In Murshidabad.”

“By hand?”

“Of course.”

“Where? Can I see?”

But he is not sure of the location. And then Ali arrives and she thinks she knows: “There’s a weaving village near Jiaganj called Tantipara.”

I glance outside. The light is turning golden. Sunset is close.

“Can you find that village?”

Ali does not seem sure. “It’ll be dark soon. We can try.”

We jump in a tuk-tuk. The driver knows where we want to go. We pass a wedding party in a horse-drawn carriage, a man with two cauldrons of fish hanging from his bicycle handlebars, and a graveyard filled with forty-seven Dutchmen. The driver slows down and starts to ask us again where we want to go. He actually has no idea. He pulls alongside another tuk-tuk and we find ourselves transferred to another driver. He is very confident about where we want to go, but only for a mile, then he too starts asking. Somehow the name now sounds different: Tantipara has become Shanisana and no one knows where that is. We drive on through Jiaganj, consulting every chai salesman and lottery vendor, all of whom seem to know where we want to go, without putting themselves to the inconvenience of actually consulting us. Our destination’s name has gone through so many permutations that it will soon be Timbuktoo.

“It’s too dark,” I say. “This is a wild goose chase.”

But Ali seems to like chasing geese. “Are we near the river?”

Google maps. No.

“Are we going north?”

No.

“Then it can’t be far away.”

The driver seems to have similar optimism. He asks small children, a drunk, a man who appears to be blind who points up a dark lane. Naturally we take it. The first light we come to is a naked bulb shining out through a barred window. Inside it looks like a spider’s vast web is hanging from the rafters. Closer inspection reveals a seated man who is magically transforming this web of fibres into a brilliant patch of colour. We have found the silk weavers.

Kevin Rushby

Photos of day 2 of Silk River India.

The Making of Murshidabad Silk

Various accounts of the history of silk in India claim that silk weaving in Bengal existed from ancient times.

Records show that the Silk Weavers of Murshidabad were operating in 18th century when Nawab Murshid Quli Khan shifted the capital of the Dewanee of Bengal from Dhaka, now in Bangladesh, to a new capital he built on the east bank of the River Bhagirathi and named Murshidabad.

Murshidabad is famous for its cowdial saris made of fine mulberry silk with flat, deep- red or maroon borders made with three shuttles.

Read more about Murshidabad silk on our website HERE.

Camera and production by Korak Ghosh, Joydeep Bhowmick and Mike Johnston.

Run time: 03:38

Silk River App – Murshidabad

Explore the Silk River Scrolls through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible