India Day 3 – Improvisation

India Day 3: Improvisation

Just before dawn we are on the riverbank about to be ferried out to our boat which floats offshore in the pearly mist. The sky and the river are same shade of grey. For once the world is hushed and almost silent. A necklace of cormorants dances across the water; a farmer brings his buffaloes to the shallows and begins to scrub them like unruly children getting a shampoo; rafts of water plants drift slowly by on their journey to the Bay of Bengal, and soon we too are sailing gently downstream. The musicians who have come to play us traditional songs begin to set up their equipment. There is discussion about cables and sound, how best to set up. This is not their normal kind of location for a concert.

I lean on the rail with Korak. The ability of the technicians to improvise, he tells me, is an example of jugaad. In England we might call it ‘winging it’. Everything will come together at the last moment by a cocktail of lateral thinking, adaptability and pure luck. “Jugaad is one of the five pillars that unite India,” says Korak, “We are good at it.”

And the other four?

“The railways, cricket, Bollywood and elections.” I’m surprised at the last one. “Yes,” he explains, “All over the country they are united by vote-buying.”

We are interrupted by a dolphin. It suddenly appears close to the boat, takes a breath and disappears. I won’t say it takes a look at us because the Gangetic river dolphin does not have eyes, nor does it have – some people say – a future, since pollution and disturbance have rendered it one of the rarest cetaceans on the planet. I don’t know if it’s an encouraging sign, but a total of three are briefly spotted during the day. I also see three types of kingfisher, two types of heron, and one type of dead buffalo, the type that floats downstream on its final journey.

You may be wondering what a Gangetic dolphin is doing in the River Hooghly, but the Hooghly is a branch of the Ganges that cuts loose from the main channel some 400km from the sea while the main river flows on through Bangladesh. The water beneath us will be Himalayan although it has aged considerably since it was a tumbling glacial stream. Now it is slow, grey and heavily burdened with vast quantities of silt which it dumps in generous thick layers, making new sandbars and islands. Our pilot steers a winding route, avoiding the shallows. On the banks farmers are busily carting the stuff away to throw on their fields. Others are shifting huge loads of dried stalks on buffalo carts. On the water men are fishing in skiffs built from a single folded sheet of corrugated iron. In this tranquil place the sheer vitality and industry of the people is impressive.

At Krishnanagar we stop and disembark. Outside the simple houses nearby racks of yarn await their turn on the home handloom. “We make saris,” a woman tells me. We get in electric tuk-tuks, known as totos locally, and set off to see a former indigo plantation, Balakhana at Maheshganj. It’s a beautiful colonnaded mansion surrounded by mango and lychee trees, so peaceful that it’s hard to imagine that indigo, a natural blue plant dye, has an ugly history. In the early 19th century when this place was built, European planters began forcing local farmers to grow indigo, the cash crop that fuelled their fortunes. Resentment grew just as fast as the indigo, and proved more dangerous, boiling over in the 1857 uprising. Three years later the enforced growing of indigo was outlawed, and thirty years later aniline dyes destroyed the business entirely. The European planters packed their bags and left.

At about the same time a local lad, having saved sufficient funds, set off for England, apprenticed himself as a boilermaker and later qualified as an engineer. He came home with bright ideas and energy, that quintessential Indian characteristic that I feel must be the sixth pillar of the nation. His family were unimpressed and, to purify the wayward son, made him drink cow urine and bathe in cow dung. Nevertheless he bought the Balakhana mansion and set up a tannery that failed, soon to be followed by a forge that failed, ceramics that – oh dear, a bit of jugaad required – failed and finally a tea plantation, that worked. Judging by the contents of the mansion today he did what I would do, should I ever make some real money: he bought a full-size billiard table and decent French bed. Today his descendants make upmarket furniture and do homestays for discerning travellers.

Back to the boat and the musicians. They have set up their sound system and are ready, but the sound is awful. What is to be done? Will the spirit of jugaad save the day? Of course it will. We abandon the amplifiers and descend to the dormitory. There lounging on the beds, we listen to their sublime unplugged renditions of traditional river songs.

Afterwards the singer, Pranes Som, tells me that these are the songs of ordinary workmen. He once heard labourers working on a bridge chant his favourite melody, The Fisherman with the Broken Boat. Why, I ask, is it his favourite? “Well, it has spiritual meaning,” he tells me. “You see the boat is the human body, broken by vices. The boatman is the human mind, capable of redemption, and the river is the journey of life.”

There is a pause. “And is that why you love it?”

He grins. “Also, I once played that song and a girl in the audience fell in love with it. Now we are married.”

So that will be my seventh pillar of India, the one that draws me back again and again: that unerring ability to make the mundane into the magical.

Kevin Rushby

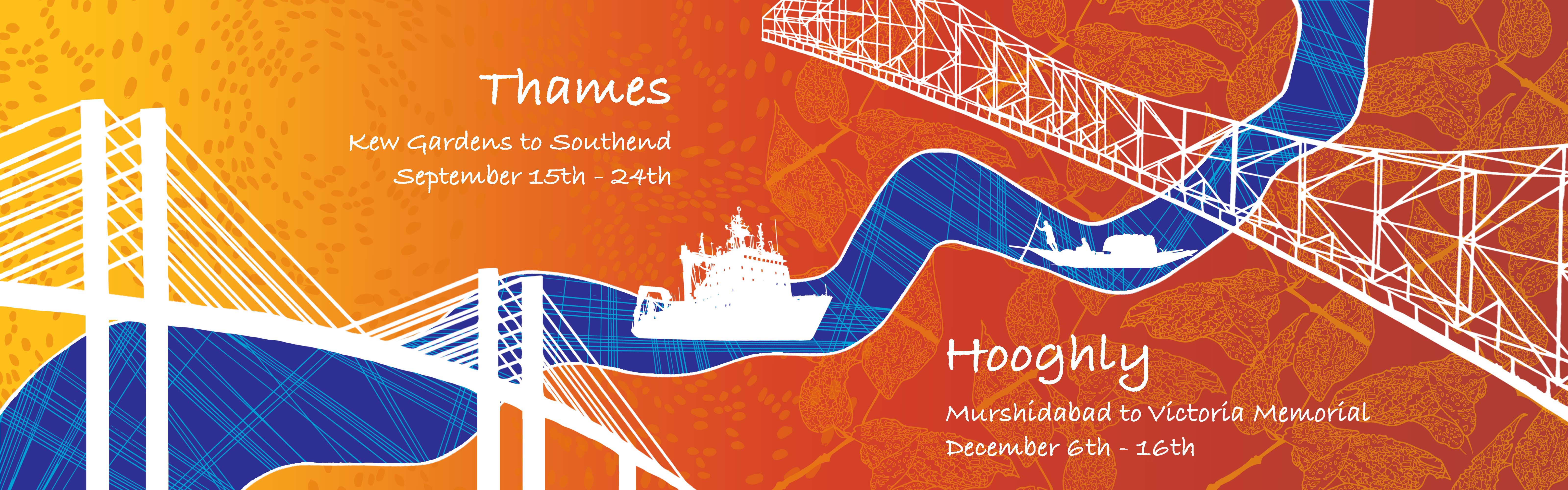

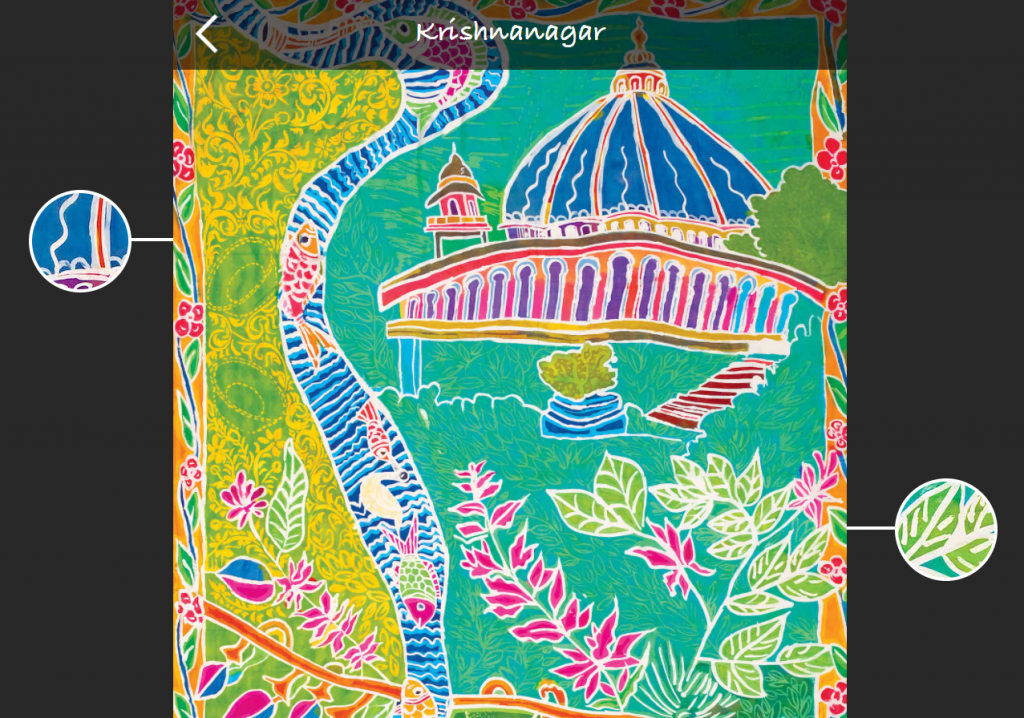

Silk River App

Explore the Krishnanagar Scroll through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible

Visit the app

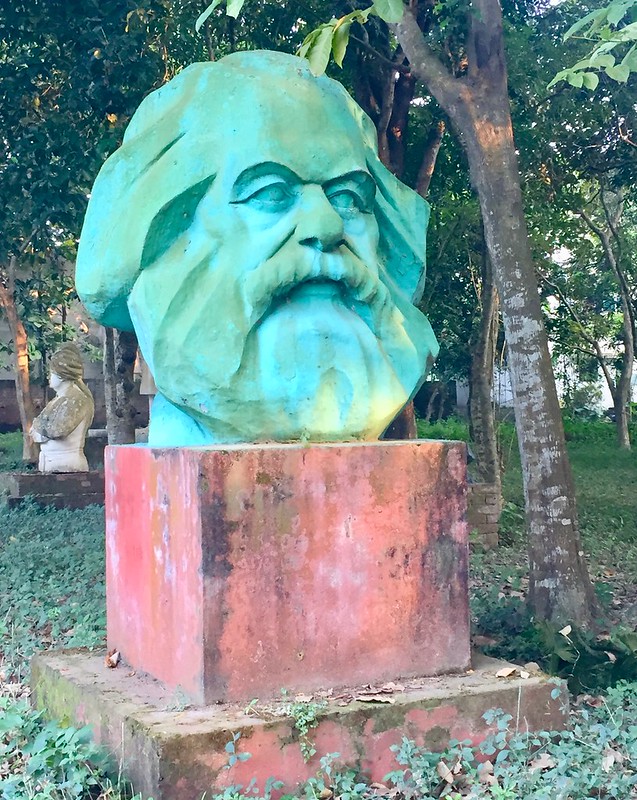

Photos below are from a research trip to Krishnanagar and Balakhana by Mike Johnston.