India Day 9 – Knots

India Day 9 – Knots

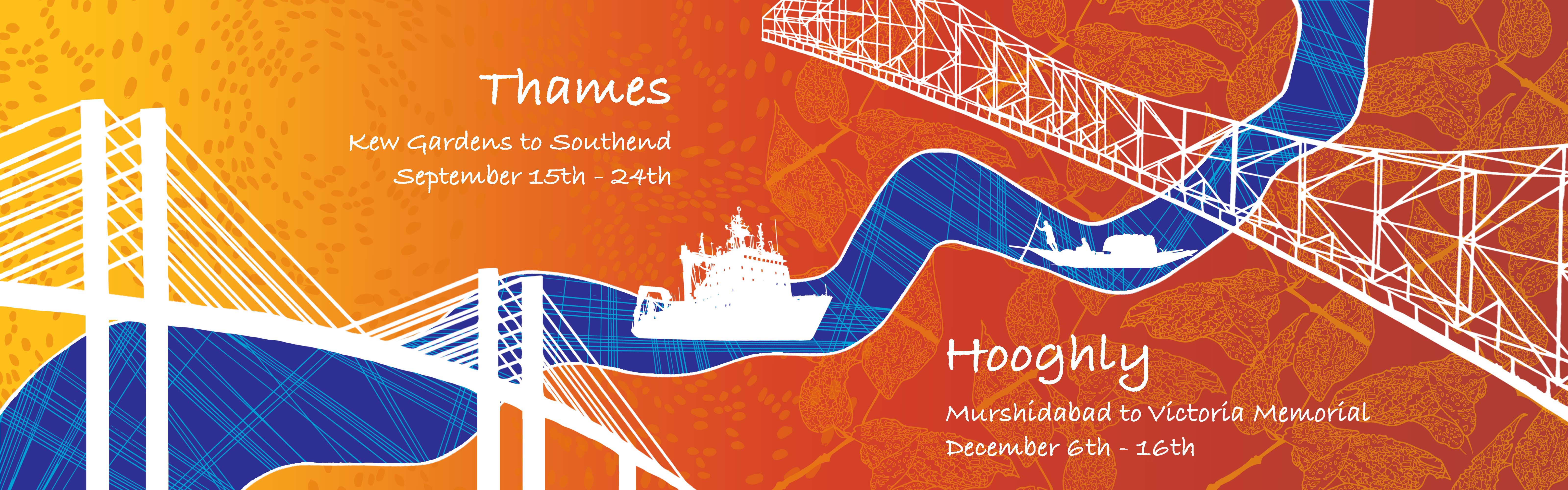

Ask any British person where in the world they would like to go, at least once in their life, and I’ll bet that a visit to India would be at the top of the list. And if there was one experience that such potential visitors would specify, it would be a journey on Indian railways. This morning we cross the Hooghly again and land near Howrah Station, a place that encapsulates all the excitement, energy and controlled chaos of Indian railways. It is the turreted temple of rail journeys.

Indian Railways is not so much a business as an empire. It employs 1.3 million people to operate more than 60,000 miles of track and run 14,000 trains per day. At Howrah we visit the museum and meet Manu Goel, manager of the Howrah division. The station, he points out, is a daily miracle of crowd control: at times there are 88,000 people on its premises, more than many small cities. It has its own police force, a magistrate’s court and an independent communications system. Its train managers do a job as stressful as any priest handling the most complex and precise of deeply spiritual rituals.

Out on the station, near the original mechanical clock, I get a sudden glimpse into a darker side of the place. A small barefoot boy is playing with a puppy: both are living on the street. At first he won’t talk to me (or rather my companion Shaunak), but when taken to the cake shop, he softens. “I had a sister,” he says, “But the junkies killed her.” How does he live? By begging. “But they beat me because I don’t make as much money as the others.” Then, suddenly, he is gone, skipping away through the crowds. Shaunak tells me that the children get here from many different areas and they have developed their own language, a melange of different dialects. If the police or railway authorities can get to them first, they have a chance, but there are criminal gangs operating too, and once in their clutches the future is bleak.

Back across the river I head off with Bagi and Bablu on an exploration. We start at Sobha Ghat. There are so many idols and figures along the water, a baffling array – to an outsider at least – but Bagi simplifies it for me. “It’s the temple in your heart that really counts.” He has an old head for such young shoulders. His father wished a medical career for him, in family tradition, but the film world’s lure was too strong, and the truth is that Bagi is born to be a producer. He has that astonishing ability to remain calm at all times and solve logistical problems with all the ease of Alexander slicing through the Gordian knot.

By the river, under a tree with a little cluster of religious objects, we find a tea shop. But this is no ordinary tea shop. Among the cognoscenti, it is a legend. The chai-wallah sits on a stone plinth in front of a carved image of Shiva. When we order tea it starts a complex and ritualistic ceremony. Cardamom and cloves are pounded, a pinch of secret spices is added, an electric fan is started that powers a charcoal fire that urges the saucepan of tea to boil into which the magic masala is sprinkled. He dabs a little on his wrists and tastes. It’s not right. Fan off. A splash of rose water and a shower of saffron. Fan on. It bubbles and froths. He lifts the pan and bangs it down in a shower of sparks. It is ready for the finale. He divides the milky tea in two and begins pouring it from one container to the other at full arm’s length. Like the priest of some weird tea-based religion, he almost disappears behind a veil of a steam and smoke. And then, selecting from a pile of terracotta cups, he produces the chai, finishing with a few flakes of saffron. I almost applaud. The man is an artist.

The family have been on this spot for 60 years. The grandfather came from Uttar Pradesh and now four brothers run the place. For anyone peckish before chai there are liti, a Bihari roasted snack, served with mint chutney and potato relish on a dish made of leaves. I have eaten in restaurants with Michelin stars: none of them can hold a candle to the Shankar chai stall at Manik Bose ghat.

Not that our adventure ends there. We walk into the narrow lanes off Chitpur Road. Here, in lanes too narrow for any vehicle, people are carving stone, spinning thread, and carving wood. Beyond a vegetable market we find a lemon market that has existed, so they tell us, for hundreds of years. The perfume of the place is irresistible. There are green columns and merchants sitting on little green sofas. “I’ve been sitting here for 55 years,” one of them says. I can understand why he does not want to go anywhere else. How long does one have to sit here in order to become a Calcuttan? A little further on we find a seller of wooden spoons who says he is a Bangladeshi. “We only came here 300 years ago.”

Later, in the taxi, we ask the driver how long it takes to be a Calcuttan. He is from Bihar, but has been a driver for 45 years in Bengal. “When I go back to see family, I am Bihari.” he says, “But when I am here… I am definitely Calcuttan.” He has sliced the Gordian knot. Two cultures in harmony. The Silk River idea in as nutshell – well, an Ambassador taxi to be precise.

Kevin Rushby

Silk River App

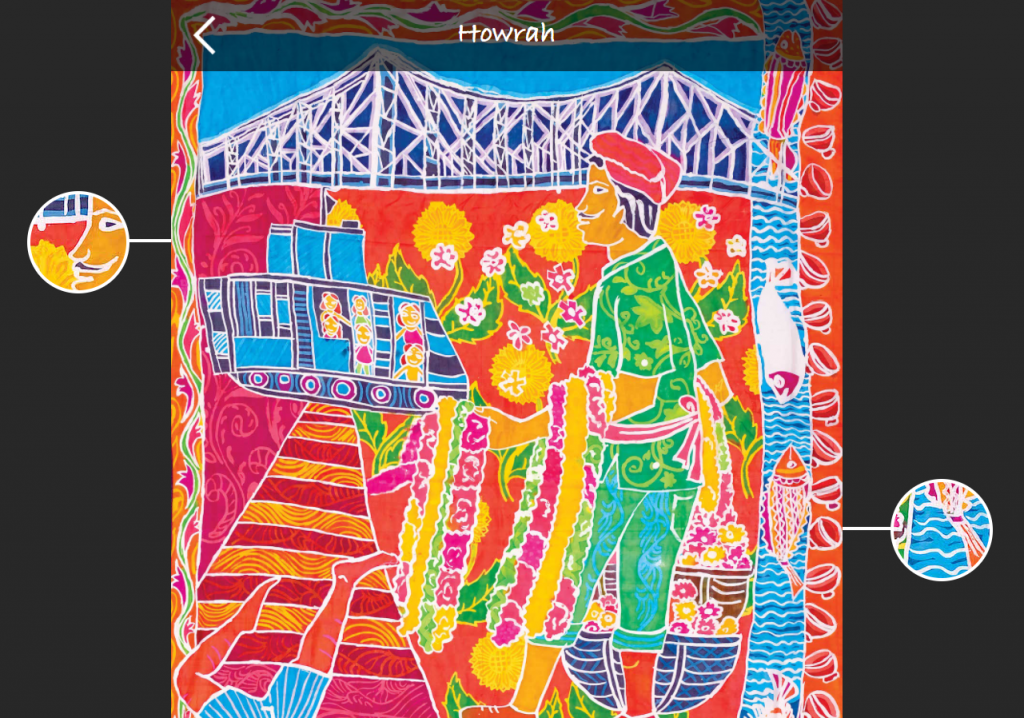

Explore the Howrah Scroll through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible.

Silk River Photos – Day 9

Photos below are from Day 9 (14th Dec) at Burrabazar and Howrah by Mike Johnston.

Photos from all the walks can be found on the GALLERY PAGE.