Day Four: You Have to Walk a Place to Understand it

Day Four: You Have to Walk a Place to Understand it

The area around London City Airport feels unloved, a mess of weed-fringed yards and fences, buildings with menacing defences designed to keep people out, or is it to keep them in? As a thin rain falls we walk east, soon picking up the riverside path, itself an uncertain accomplice, tip-toeing its way around obstacles like a trespasser, easily escorted away from its proper home by the water.

We cross the lock gate bridges for the old Royal Docks where once the Cunard liner Mauretania, largest and fastest ship in the world, squeezed itself inside with inches to spare. Now this land is being redeveloped, the great liners are all gone and the river seems superfluous to the aims of the developers, only good for sunsets.

We enter a strange landscape where a Porsche dealer is neighbour to a strip of woodland filled with rubbish: a duvet hangs in a tree, a tiny vole lies dead on the cycle path. A small bump in the path is the course of the Great Sewer of London, a construction that ended cholera outbreaks in the capital. Its engineer, Joseph Bazalgette, knew the value of art: he made poo-pumping stations that resembled Byzantine churches. Now they are Grade 1 listed. Our own silk banners hold his artistic values aloft as we pass piles of rubbish and a steel fence with a shopping trolley jammed into it – actually that might have been an early Gormley.

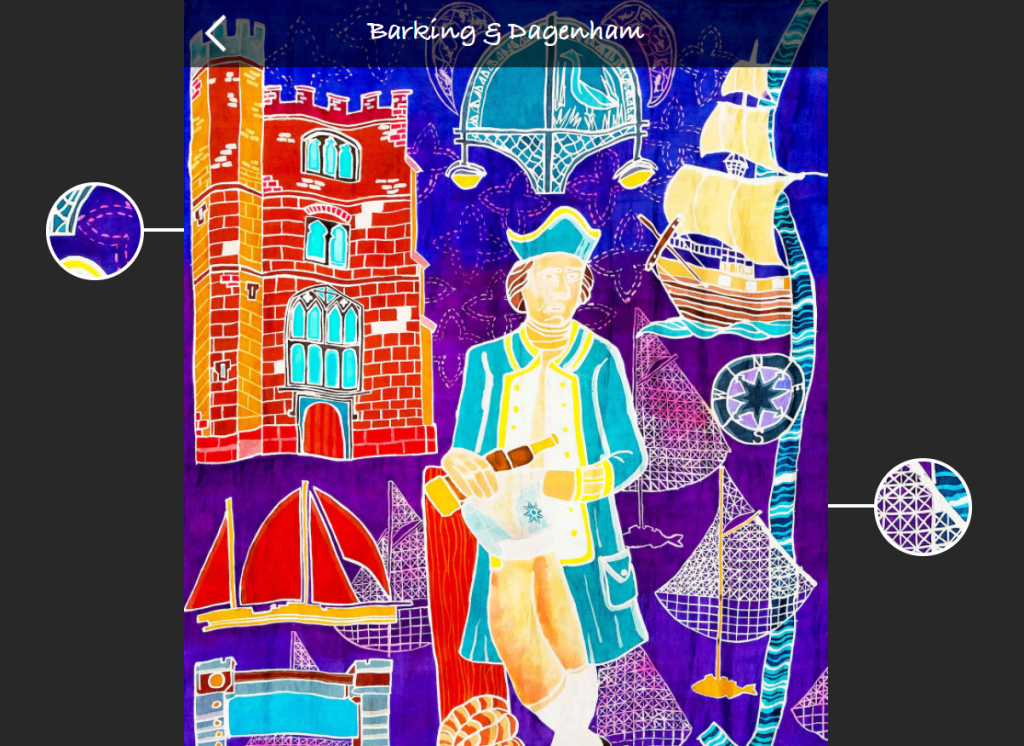

And then abruptly we enter a nature reserve, curl around the banks of the River Roding and emerge in Barking. At the abbey in the centre, from where William the Conqueror once ruled Britain, we are greeted by enthusiastic locals eager to carry the banners. We have more flags now, but there are many willing hands to help. There is a growing sense of energy and purpose, like a river approaching the sea.

“Look,” says Charlie, one of those new helpers, “You have to walk a place before you can really understand and care for it.” I am seeing that all the time on this journey. I used to think that London, at least the interesting part, ended at Greenwich. Now walking the Silk River route has broken down that prejudice forever. I’m also building a mental map of London that includes these forgotten zones, a map that is dotted with interesting locations worth visiting. In Barking that means the abbey and the artists colony with its excellent café. This is an area scarred by deprivation and economic failure, but regeneration is coming. “Artists can help with that,” says Carlos, a Colombian academic and architect who has come to join the walk for a day. “They bring a different perspective to planning and heritage – something unexpected, some imagination.”

Down at Barking Riverside where over 10,000 new homes are emerging from the contaminated land of a former power station, we sit by the Thames. There is a seal lazily flapping his tail at the cormorants. Porpoises are sometimes spotted. “When I was kid down here,” says Jim, a man who has been here since the early 1960s, “We’d run along the bank waving to the passing tug boats. We were like the Railway Children. Redevelopment is a good thing, but I want to see the river used. It’s all there – it just needs people with a bit of imagination.”

I think I know who they might be.

Kevin Rushby

Silk River App

Explore the Barking & Dagenham scroll through the art, images and reflections of the people that made it possible

Photos from the Silk River walk in Barking and Dagenham, 18th Sept, by Mike Johnston.